We have plenty of evidence at this point to suggest that Spurs’ underperformance since around the 10th week of the season is mostly explained by injuries, especially injuries to our starting center backs and goalkeeper (if you’re interested in digging into that evidence, you might want to read some of my work on it here and here).

But there’s also the looming question of whether Ange Postecoglou himself is at fault for Spurs’ injury crises, particularly the high volume of muscle injuries Spurs players have sustained to this point in the season.

Demonstrating causality for a question like this is complicated because there are so many variables to consider. Do we have an unusually high number of players who are anatomically susceptible to muscle injury? Are we seeing the results of a compounding factor, such as suspensions, illnesses, and knocks reducing the squad size to the point where player overuse in a weakened squad leads to muscle injuries? Have we just played too many games relative to the size of our squad and the age and experience level of the players who are logging the most minutes for the past three months (Spurs are tied with Liverpool for the most games of any Premier League team this season—40 games as of today—which is nearly 8 more games than the league average of 32.7)? And other considerations beside these.

Others have suggested that Spurs’ high number of sprints both in and out of possession, coupled with the intensity of our high press, are responsible for our high volume of muscle injuries. Though others have also shown that Spurs aren’t sprinting that much more than other clubs, in effect an average of 1-2 minutes more per match. So there’s a question here about how much more intensity—measured in sprints—is needed to demonstrate causality.

What this suggests to me is that even sprinting data is inconclusive as to whether Ange’s way of playing is causing injury.

Rethinking the Measurement Timeline

So far we’ve been looking for proxy variables to demonstrate how or whether Ange Postecoglou’s way of playing is causing a disproportionate number of muscle injuries, so we can blame him for Spurs’ injury crisis.

Complexity of the causal claim aside, one flaw in this approach is that it effectively rules out the kind of variance you should expect in injury rates across the league and over time. Put another way, the fixation on Ange’s Spurs ignores what’s happening at other clubs and what might happen in the long run of the season. It assumes the conclusion (there must be something Ange is doing wrong to cause all these injuries), when it’s perfectly possible that Spurs to this point in the season—especially given their league-leading match volume—are just at a high point in league muscle injury variance while others are at their low point.

So, even if we look at metrics such as total number of injures, total number of muscle injuries, total number of days missed due to injury, total number of games missed due to injury, and then we run all kinds of analyses on these metrics against proxy variables such as sprints or running distance, we’re ruling out another possibility.

That possibility is simply that, descriptively, Spurs’ don’t get systematically more muscle injuries than anyone else (they just happen to be a high point in muscle injury variance at the time we’re taking our measurements). Not to put too fine a point on it, but you can be as sophisticated and thorough as you want with your proxy variable analysis (sprints, etc.), but if your descriptive data (how many muscle injuries, etc.) is from an unrepresentative sample or time point, then you won’t get a good explanation for what’s happening.

Another Way of Answering the Question

To address this weakness in the ways people have gone about answering the question so far, I’ve asked and answered another, simpler question. Instead of starting with why questions—what explains the injuries, causally—what if we return to the do questions—do Spurs actually have the most and the highest percentage of muscle injuries? Because if they don’t, then what is the observation we’re trying to explain at this point?

Anecdotally, if you’ve been following the Premier League, you’ve probably noticed a lot of high-profile muscle injuries lately, as well as other teams struggling with emerging injury crises just as Spurs have started to get injured players back.

So I’ve taken this anecdotal cue and created a systematic snapshot of where every Premier League team is with injuries at this point in time.

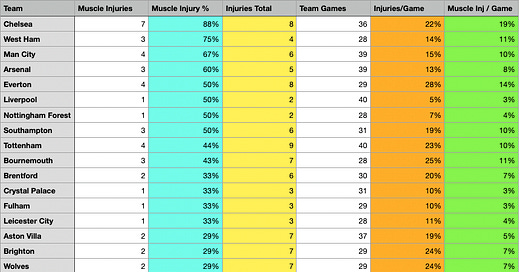

The last time I took this snapshot, a little less than a month ago, it looked like this:

As of 20 January, Spurs had the most total injuries in the Premier League, with the 6th highest percentage of their injury total that were muscle injuries. So, even at the height of Spurs’ muscle injury issues—and of Spurs’ broader injury crisis—they were not far above the league median for percentage of injuries that were muscle injuries.

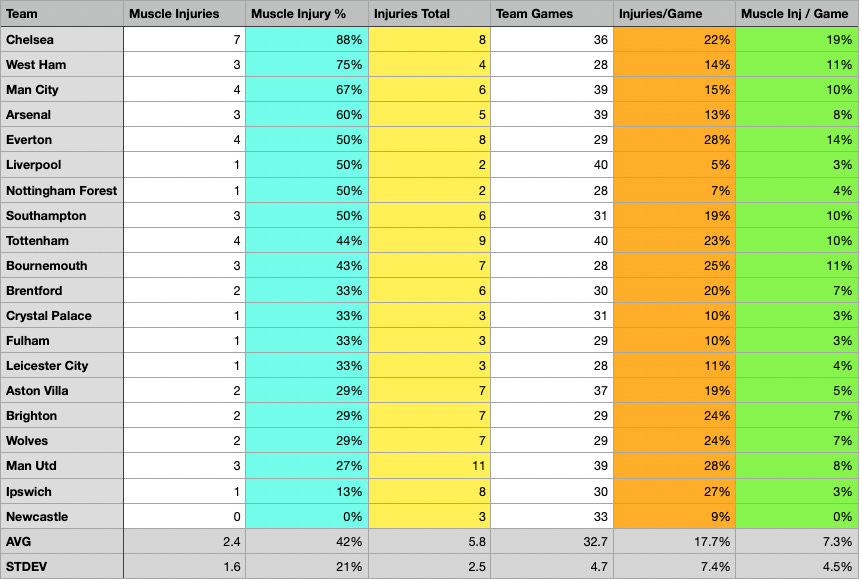

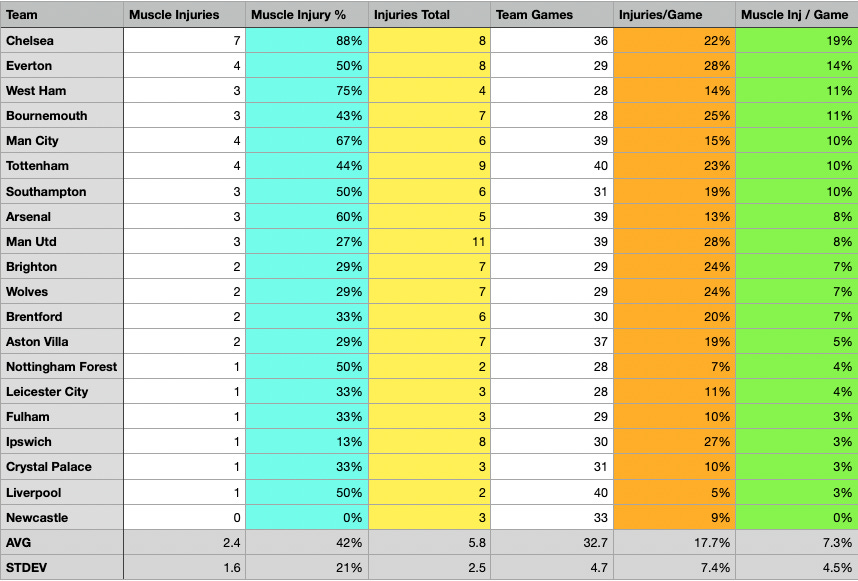

I’ve made a few minor tweaks to the table and updated it as of today, 17 February, with some telling results. Below is the updated table sorted by percentage of injuries that are muscle injuries. As you can see—just descriptively—Spurs are mid-table for muscle injury percentage, with 8 teams above us with a higher percentage of their injuries being muscle injuries:

If we sort the table by percentage of muscle injuries per game played—in an effort to weight the overall percentage of muscle injuries against volume of games, under the assumption that more games equals more wear and tear equals more risk of muscle injury—we see that Spurs are tied for the 5th highest, behind Chelsea, Everton, West Ham, Bournemouth, and even with Manchester City and Southampton:

Here are a few key discussion points based on the data above:

Spurs have never been an outlier in terms of muscle injuries, but at this point are not even especially beset by muscle injury, having come down to the middle of the pack by this metric. Chelsea are a clear outlier, even with fewer games played than Spurs. Even taking the raw count of muscle injuries per team at this point (so, ignoring muscle injuries as a percentage of total team injuries), Spurs are within one standard deviation of half the league:

The teams above Spurs in muscle injuries per game are the outlier Chelsea, plus a few who’ve been on the lower end of games played, which suggests this metric is especially sensitive to lower numbers of games played (which makes sense: if your n games played is on the low side, just 2 or 3 muscle injuries can inflate your percentage). So, muscle injuries per game, as a metric, probably works a bit better as a signal of what’s going on when applied to teams who’ve played a higher volume of games, i.e. have a larger game sample. In that sense, Spurs are right around City and Arsenal, which is to say they are not outliers even among those who’ve played a lot of matches. The low outliers in this regard (Aston Villa, Liverpool) may just be at low points in the league variance or may just have deeper, more experienced squads to handle the high volume of games).

Among the teams who’ve played a high volume of games—Chelsea, City, Arsenal, Liverpool, Aston Villa, and Manchester United—only the last two have a lower percentage of injuries that are muscle injuries than Spurs. Which is to say, right now, at this point in the season, Chelsea, City, Arsenal, and Liverpool all have a higher percentage of their total injuries that are muscle injures than Spurs.

My claims here aren’t meant to be explanatorily conclusive—as in, I’m not claiming to have demonstrated the cause of muscle injury, nor am I claiming to have ruled out the contributions of sprints or running volume or other measures of intensity as answers to the question we started with.

However, what I have shown is that, simply in terms of the descriptive elements of the question, i.e. not the why question of causality but the do question of what’s the case at this point in time, Spurs are neither outliers nor especially beset with muscle injuries. Also, lots of other teams are experiencing a particularly high rate of muscle injuries right now. Had they experienced these levels of muscle injuries before Spurs, instead of after Spurs, would the press have been dogging Enzo Maresca or Mikel Arteta about whether their methods are causing high rates of muscle injury? This is simultaneously an informational and a rhetorical question.

Accordingly, for now, I remain skeptical that play style has much to do with muscle injuries. I think it’s more likely that it’s a complex question in terms of causality and there’s lots of variance over time across the league (while perhaps little variance at any given point in time between the high and low ends of muscle injury incidence, as you can see from the standard deviation figures above).

Spurs have been hit especially hard so far this season, but that doesn’t mean others won’t be hit just as hard in the second half of the season, especially as volume of games catches up some teams who haven’t played as much as Spurs so far, and as simultaneous injuries start to compound the problem by taxing the remaining players with overuse.

Another great post

Interesting article as usual Prof. I have a doubt. Why did you consider only muscle injuries for the analysis? And what constitutes muscle injuries? I'm guessing you addressed these 2 questions previously and I missed them. If so, could you please direct me to those articles? Cheers!