On 30 October, Spurs took a thrilling victory at home against Manchester City in the fourth round of the league cup. Before that match, City were on a run of victories, business as usual for them. After that loss to Spurs, City commenced a downward spiral from which they’ve yet to recover.

The joke is that Spurs broke City, but there’s a way in which City broke Spurs, despite the result.

Micky van de Ven went down injured in that match on 30 October. In the following match, a 4-1 victory against Aston Villa, Christian Romero left with an injury. A couple weeks after that, Vicario injured himself (again against City) and has been out since. Then a couple weeks after that, after playing without our two starting center backs, we lost a third center back in Ben Davies against Bournemouth in a 1-0 loss.

You could call this period the beginning of Spurs’ injury and availability crisis this season, an ongoing crisis that’s only gotten worse with a long-term injury to Destiny Udogie. Not only did we lose both starting center backs and a third of our four CBs in the squad; we had also lost our starting keeper and were missing Rodrigo Bentancur due to suspension and Mikey Moore due to illness. Wilson Odobert and Richarlison had been out and still haven’t returned.

Thus marked a turning point in the season at which, during match week 10, Spurs sat 7th in the table, just 3 points off 3rd place Nottingham Forest, with the second-best goal difference in the league:

Soon thereafter, Spurs’ results and table position started to slip:

The Simplest Explanation

It’s tempting to develop elaborate theories to explain Spurs’ run of poor results, especially theories about managerial tactics and decisions. This is the Era of Big Manager, in which managers are major footballing celebrities in their own right, and in which we find a concomitant tendency to give outsized explanatory weight to the things managers can control. But managers can’t control everything.

In Spurs’ case, Ange Postecoglou can have some influence over squad fitness, in the way he sets up training and in managing playing time. Likewise he can influence which players the club bring in and can set the agenda for what kind of squad he wants. But he can’t single-handedly prevent injuries to players, nor can he pick and choose which players get injured and when, nor can he dictate to the executive leadership and the Director of Football Operations all of his squad depth desiderata and receive exactly what he asks for, like a spoiled child at Christmas.

So in what follows I’m going to direct you to the evidence in front of our eyes: Spurs’ slide down the table is more about the injury crises than any other factor. The injuries explain the results.

Before the Breaking Point

By match week 10 (against Aston Villa, the first Premier League game after the van de Ven injury and the game in which we lost Romero to injury as well), Spurs were not just within touching distance of top-3, but boasted outstanding underlying numbers.

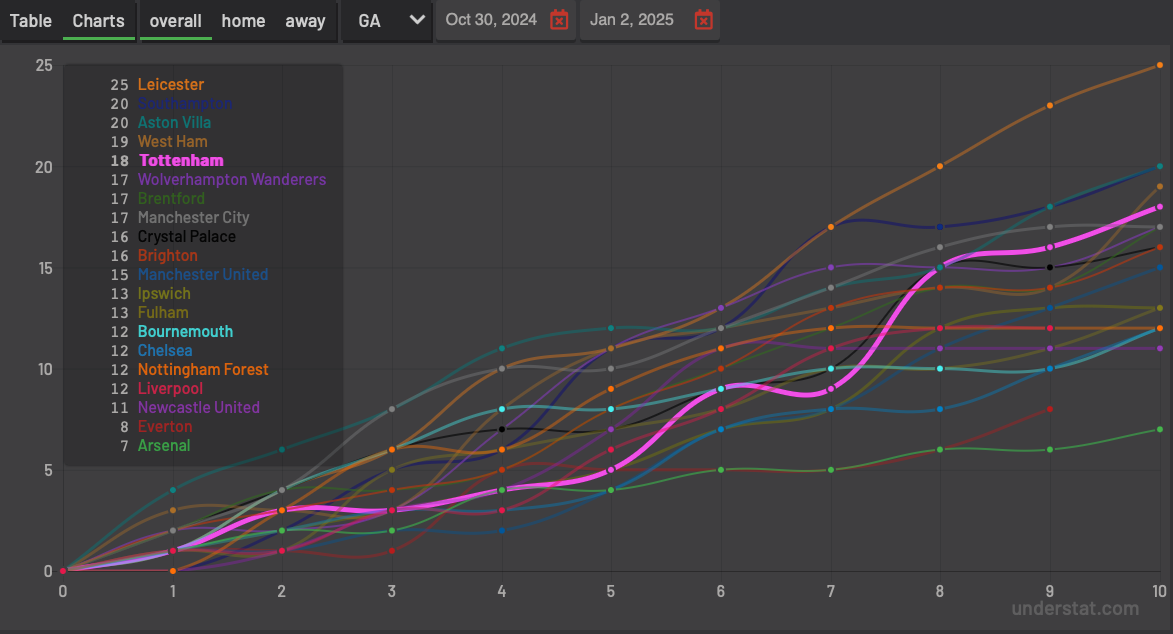

Before 30 October, defensively, Spurs were tied (with Arsenal and Newcastle) for the 4th fewest goals conceded in the Premier League (charts that follow are courtesy of understat.com):

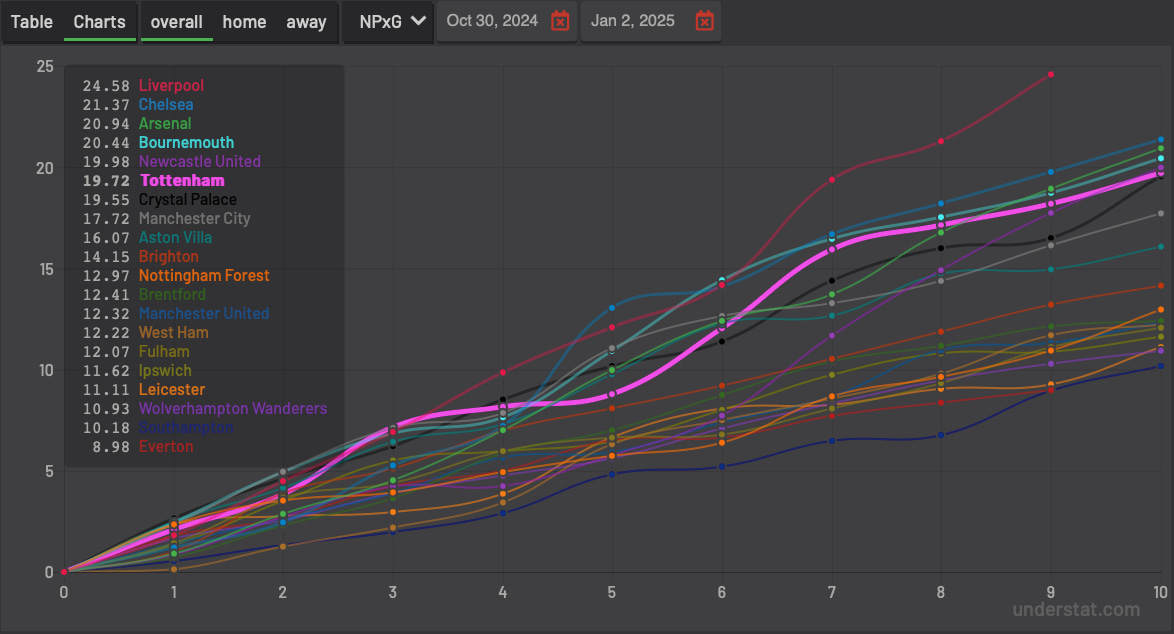

In terms of expected goals against, Spurs were second only to Liverpool:

The press was also humming before we lost both of our starting center backs. Passes per defensive action (PPDA) measures how many passes your opponent can string together before one of your players intervenes to stop them. The lower the number, the more effective the press. Spurs topped the league in PPDA to that point, by a significant margin at that:

Offensively, Spurs had scored the 3rd most goals in the league (tied with Brentford at that point):

And were top of the league in non-penalty expected goals:

Spurs were also playing the 3rd highest average defensive line, and were pushing our opponents to the 2nd deepest average defensive line in the Premier League. In other words, we were controlling games and controlling territory.

We had also settled into a possession-based style of play and buildup method, with relatively stable and few long passes attempted:

After the Breaking Point

To put it mildly, once Spurs started to sustain heavy injuries to our goalkeeper and back line, things started to look radically different. As you can see above, past the Villa match (again, the first Premier League match once the injury cascade began with van de Ven and Romero), we’ve played long more often.

But more importantly, from 30 October onward (let’s call this the injury crisis period), Spurs’ begin conceding a skyrocketing number of goals. In the period between 30 October and now, Spurs’ 18 goals conceded is the 5th worst in the Premier League:

And it’s not just bad luck (or variance). Our expected goals against has been the 2nd worst in the league; only Southampton have conceded more xGA:

I don’t mean to put too fine a point on it, but Spurs went from being one of the best defensive teams in the Premier League to one of the worst, and that happened once we lost our two starting center backs and our starting goalkeeper.

You might be tempted to stop reading at that, but let’s go on…

Our press is also suffering, which is not surprising, given the lack of options off the bench to rest tired legs. What was by far and away the most intense and effective press in the Premier League through match week 10 has since dropped to the 8th:

A bright spot over this period is that Spurs have continued to score goals, more goals, in fact, than everyone but high-flying Liverpool:

Nevertheless, Spurs have gone from the most dangerous chance-creating attack in the league to 6th in NPxG:

What to Make of This

US political strategist James Carville famously coined the phrase ‘It’s the economy, stupid!’ in 1992. Carville’s quip was about seeing what’s right in front of your face before looking to abstruse and complex theories to explain what’s going on (in an electoral cycle as in a football season). To modify the phrase for the case of Spurs from 30 October to present: It’s the injuries, stupid!

Well, wait, I don’t think you’re stupid! If you’re reading this then you’re probably pretty smart. But I think the evidence points to injuries as the best way of explaining Spurs’ recent downturn, both in results and in some key underlying numbers.

You don’t just magically go from top or near top of the league in all of these important metrics to middle and in some cases near the bottom in those metrics—with matching results—at the exact point when you start to take on injuries to key personnel, especially key defensive personnel. In particular, you don’t go from being one of the very top defenses in the Premier League to being one of the worst because of manager tactics or personnel decisions.

No, that happens when you lose the vast majority of your defense to injury.

I’d be more skeptical of this simple explanation if it also didn’t make footballing sense. But it does. That is, we’re not just reading numbers like tea leaves. The numbers just demonstrate what we’re seeing with our eyes, which is that:

A possession team that struggles to keep possession and to play out from the back—so has played it long lately, more often than usual—is not going to be as effective either in keeping the ball and managing games or in avoiding the opposition press. Amid the injury crisis, Spurs have dropped to 7th in danger of possession lost, meaning when we lose the ball in buildup and attack, we’re losing it in dangerous areas and opponents are generating threat against us:

A tired team that ordinarily relies on high pressing, both to defend from the front and to create chances from high turnovers, won’t do either of those things effectively when it can’t press as normal, due to fatigue, and can’t rejuvenate the press late in the game with fresh legs. Spurs are now playing just the 8th highest average defensive line height, down from 3rd:

A backup goalkeeper and at most 1 or 2 of the 4 players in the first-choice back line won’t be as effective at defending.

A tired squad won’t be first to the second ball.

A tired squad won’t be as sharp at finishing chances or making the right final pass.

Looking at all of this in the Era of Big Manager, you might be tempted to suggest that Postecoglou should just adapt the playing style to deal with the injury crisis. However, what the evidence above suggests is that on some level he already has—we play a deeper average defensive line, we play the long ball more, we press less, and we hold less possession—and the results are the worse for it.

That’s because there’s simply no way of getting around a thin squad spread across 3, perhaps soon to be 4 concurrent competitions, with ongoing long-term injuries to key players. Ask yourself if any other team—even those with superior squad depth—could maintain their way of playing and their results without 3 of their 4 center backs fit, without their starting goalkeeper too, and with a slew of injuries and suspensions on top of that, including long-term injuries to 3 attacking players, leaving just 4 more to play across all 3 front-line positions in all competitions.

The answer is probably no.

This is so well written. I wish mainstream media talked more about the injury crisis.

I was thinking about squad depth and your comment on wages / no. of players on big contracts. Swiss Ramble put out some figures today for West Ham finances which included wages to turnover ratios, wages and revenue figures for all PL clubs. Spurs have the (financially) best wages to turnover ratio in the League at 46%. League average is 73%, other 'Big 6' clubs have 61% average. Tottenham 2023 revenue 4th highest at £550m, Tottenham wages 5th highest at £251m. If our wages to turnover ratio were increased to the Big 6 average at 61% that would add a further £86.7m to the budget, an increase of 35%. Thats the equivalent of 16 more players on £100k pw contracts: a whole lot of squad depth. Alternatively that's 8 more players on £200k pw contracts: a significant step up in quality. This really ought to be the direction of travel for the club and if the purple and gold brigade want to questions the Board's ambition this is where they should focus. Spurs still recorded a £90m loss in the 2023 accounts, so we can't just get there overnight and we have a big stadium related interest bill to pay that other clubs don't (c.£20m pa), but I do think that over the next few years there is plenty of scope for Spurs to start paying a lot more in wages. We can afford better players on bigger wages.