Results this season under Ange Postecoglou have not been good enough. That’s technically an opinion, but let’s treat it as a fact for the sake of what follows. Let’s say we know that results haven’t been good enough the same way we know the Earth has just one moon.

Now, for some fans, just knowing this provisional fact about Spurs’ results this season is enough to think we should sack the manager. But I suspect even those fans who think that way would be open to having their minds changed if we had more information about why results have been so unacceptably poor this season, and if that information pointed us in the direction of another culprit.

In other words, when we need to make difficult decisions, in football, in research, and in life more generally, we don’t just decide on the bare facts of the matter. We tend to want explanations for those facts before we make a big move, because the explanations matter. If we don’t know what’s causing the fact we’ve observed, then making a decision based on that fact might leave us right back where we started, or even make things worse.

Let’s put this in Spurs context: Our results this season might be poor because Ange is a poor manager. Or they might be poor because ENIC and Levy are poor stewards of the footballing side of the club. Or they might be poor because of ‘bad luck’ or variance. Or they might be poor because of inopportune and extended injuries in the squad. Or any number of other reasons.

In reality, the problem is almost certainly some combination of these things. But in any case, being able to explain why results are poor is really important for the next decision the club make. Because if the plurality of the problem is ENIC / Levy, then sacking the manager might not get to the source of the problem, and we end up right back where we started. And that works bidirectionally: If the plurality of the problem is the manager, and we decide to keep him on for another season, then again we’d end up right back where we started, or worse.

The point is that the simple fact of the results being poor is not enough to determine what we should do about it. ‘The results are poor, therefore sack Ange’ is no better a claim than ‘it’s sunny today, therefore throw away my raincoat.’ If you can’t explain the phenomena you’re observing then you’re not in a good position to act.

Experiments Are Not Easy

What’s happening right now at Spurs is a kind of experiment. We’d like the experiment to be over on a timeline that suits us. Some would like the experiment to end with confirmation that Ange is the right manager for us; others would like the experiment to end with confirmation that Ange needs to go. A lot of people in both camps would like to believe—again for the sake of convenience—that we’ve experimented long enough.

In reality, however, experiments aren’t easy, and you don’t just get results because you want them. Over the course of experimentation, it’s common to get conflicting, often baffling results, results that are difficult to explain. Your trend line might look really tidy and then, suddenly, you have what look like anomalies you can’t yet explain. You want to know now, but reality isn’t cooperating.

Of course, Tottenham Hotspur under Ange Postecoglou are not a real experiment. But there are similarities. Sometimes we look like world-beaters, sometimes like relegation fodder. Some matches we ruthlessly control, others we let slip away. Some results—against the likes of Manchester United, Manchester City, Liverpool, Aston Villa—demonstrate we can compete and win against the very best, while others—Crystal Palace, Ipswich, Everton—make it seem like we belong in the bottom third of the table.

Such results really should be baffling, yet too often we like to speak about them in broad strokes: ‘Ange is out of his depth!’ ‘Not good enough!’ But again, what we really want to know is why. Why is this team that smashes City 4-0 at their place down 3-0 at halftime to Everton? We already know that something isn’t right here, that this is not acceptable, that we want to become the kind of team that both beats top-end competition and takes care of business against weaker opponents. We have a lot of thats but are short on whys.

Results are Results

The phrase ‘results are results’ has two meanings. One is the common and colloquial meaning: results are what matter most and no matter how many different ways you look at it, no matter how many mitigating factors you can come up with, the results are what matter most, and the results speak for themselves.

The other meaning is a bit more subtle: results themselves are consequences of prior actions. They are results of something else, as in they result from something else.

The colloquial meaning of ‘results are results’ is meant to turn off the explanation faucet and stop the why? from flowing. The other meaning has the opposite effect: it’s an invitation to explain why the results are what they are. What caused them to be this way and not some other way?

The Case Against Ange

So, one possible explanation for Spurs’ results being unacceptably poor is that Ange Postecoglou is not a good manager, or not up to the level of managing at a club like Tottenham in the Premier League. That explanation goes something like this:

Ange had an exceptionally strong run of 10 games last season to start his career at Spurs, which we can attribute to ‘new manager bounce.’

Since those first 10 games, Spurs have played 50 more in the Premier League, winning 19, drawing 7, and losing 24, during which period we’ve scored 96 goals and conceded 88, for a goal differential of +8. The reason for such poor results after the first 10 games is that the ‘new manager bounce’ wore off and Ange has been found out tactically.

Faced with adversity, Ange does not offer any tactical modifications to how Spurs play, which shows that he’s out of his depth and doesn’t know what to do. He insists on playing a suicidal high line that makes Spurs easy to play through.

The intensity that Ange demands, both in training and on match days, is responsible for the high number of injuries Spurs players carry, especially muscle injuries. That, and Ange doesn’t properly rotate the players, especially failing to play youth players, contributing to injury and fatigue in the squad. Therefore, in whichever ways you could point to injuries as mitigating factors in our run of poor results in the last 50 Premier League games, the injuries are still the manager’s fault.

The Case Against Injuries

Since ‘the problem is mostly Ange’ and ‘the problem is mostly injuries’ are directly related—especially because the case against Ange typically involves some version of the claim that the injuries are Ange’s fault—this section will follow the same structure as the section above. Take items (1) through (4) above as components of an explanation that Ange as a manager is the main cause of our poor results. Accordingly, take items (1) through (4) below as parallel components of an alternative explanation that injuries are the main cause of our poor results.

The idea of a ‘new manager bounce’ has been empirically investigated and largely shown to be a myth. If you’re serious—and intellectually honest—about explaining Spurs’ poor results after the first 10 games of last season, then the first question you should be asking is ‘Why the cutoff of the first 10 games?’

After all, Spurs’ record after the first 11 games of last season was 8W - 2D - 1L, good for 2nd in the league, a point behind City in first. Even 19 games in, Spurs were 11 - 3 - 5, having won the same number of games as Manchester City at that point. Only 3 teams—Villa, Liverpool, and Arsenal—had more wins than Sours—12 wins to Spurs’ 11—halfway through the season. Spurs sat 5th, just 6 points off Liverpool at the top of the table and 3 points off Villa in 3rd.

So, given that performance level 19 games into last season, not just relative to the red-hot 10-game start, but relative to other top teams in the Premier League, why does the case against Ange keep going back to those first 10 games? One simple answer is that Spurs went unbeaten in those first 10 games, though I doubt anyone would argue that eventually losing a football match in the 11th game of the season means the manager is on thin ice and has been found out. So what exactly happened in the 11th game of the season that made it such an important cutoff point for those making the case against Ange?

I suspect you already know what happened in that pivotal 11th match—Spurs got smashed 4-1 in a catastrophic match against Chelsea. But let’s recall more closely what happened in that match. Spurs jumped out to a 1-0 lead before Chelsea were awarded a penalty for that Christian Romero challenge in the 33rd minute, for which he received a red card (I say that challenge because since then, players similarly catching an opponent with their follow through while playing the ball hasn’t been given as a foul, let alone a penalty and a red card). Cole Palmer converted the penalty, and shortly thereafter Micky van de Ven pulled up with a hamstring injury just before the end of the first half. Spurs went into the half against Chelsea at a 1-1 draw, then played the second half both a man down and without either of their two starting center backs.

This detail is important and goes to the question of whether the Chelsea match marked the point at which Ange had been ‘found out.’ It certainly marked the point at which the narrative about Ange’s Spurs playing a recklessly high line went into overdrive. But it also revealed a serious vulnerability that’s hard to put down to the manager.

As Joel Wertheimer points out, “Spurs have played at about a 70 point pace with Van de Ven and Romero on the pitch together under Postecoglou.”

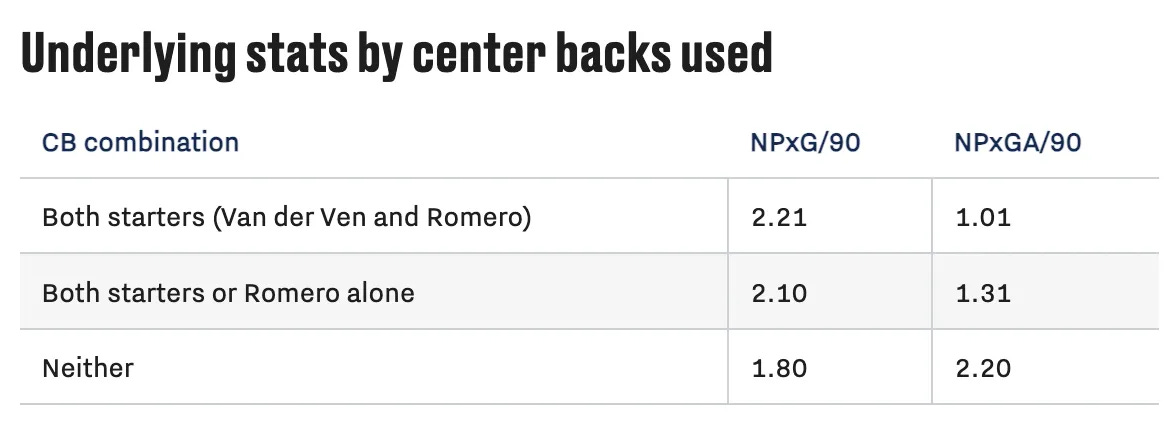

Cartilage Free Captain corroborates, demonstrating a massive difference in our defensive record under Ange—well beyond the first 10 games of last season—based on whether we have both or even just one starting center back in the team:

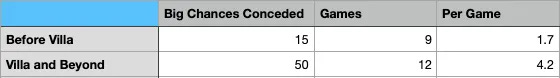

I’ve shown similarly for this season that, around the same time as last season, when we’ve lost both of our starting center backs, our defending started to take a catastrophic hit. With both starting center backs and our starting goalkeeper, Spurs this season surrendered among the fewest big chances in the Premier League (for comparison, the leaders are Forest and Arsenal at 1.4, then Liverpool at 2). But once the injuries hit, we started conceding more than double that amount:

Beyond these metrics, I’ve also shown that there’s been a massive difference in Spurs’ performances before and after the injury crisis set in this season. Again, for the purposes of explaining the poor results, I think the evidence is simply too overwhelming to ignore.

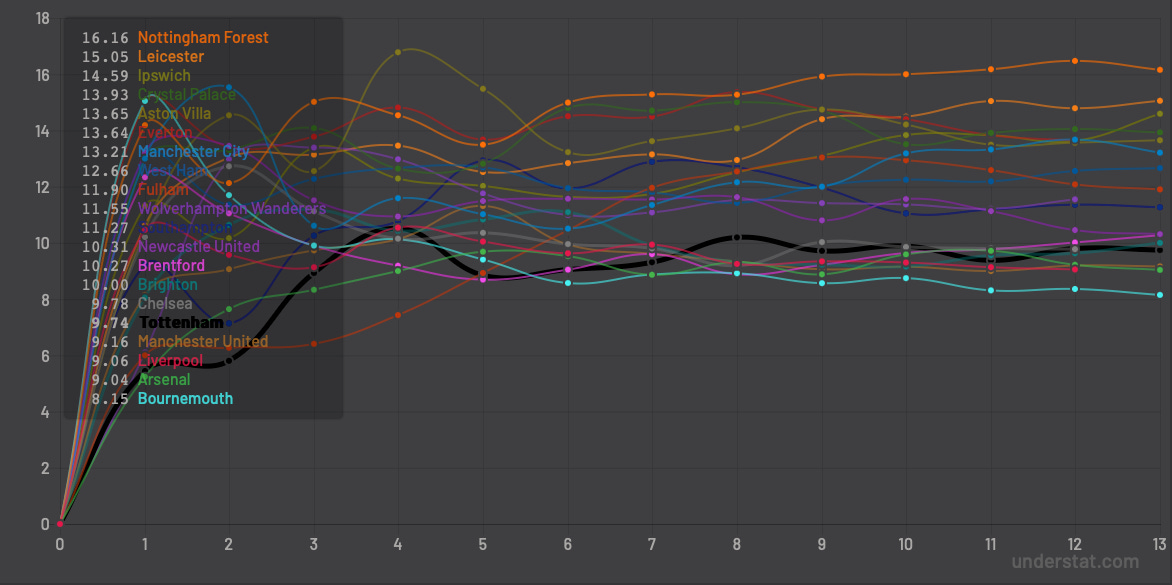

Ten games into this season, Spurs were tied with Arsenal and Newcastle for the 4th fewest goals allowed in the Premier League. That was a slight underperformance, because Spurs were also second in the Premier League only to Liverpool in expected goals against. Offensively at that point, Spurs had the 3rd most goals in the league and were top of the league in expected goals. At that point, incidentally, Spurs were playing the 3rd highest average defensive line in the league.

Shortly after the injury crisis sets in—especially the loss, once again, of both of our starting center backs—it’s night and day. Spurs’ goals conceded plummeted to 5th worst in the Premier League, and expected goals against down to 2nd worst. As of today, Spurs have surrendered the 7th most goals in the league and the 6th worst xGA (grotesquely, a slight rebound from the period immediately after we lost our starting CBs and goalkeeper, among others). Likewise, as of today, Spurs’ attack remains strong, with the 2nd most goals and the 5th highest xG in the league. Notably, however, as of today, we’re playing the 8th highest defensive line.

So I think the case against Ange—as an explanation for poor results—starts to break down in favor of the case against injuries at one key point in particular:

Whether we’re talking about actual results, as in points taken from matches, or underlying metrics that strongly signal how competitive a team is, the manager stays constant but the results change based on injuries.

In other words, injuries are the variable that most clearly impacts results. If you want to claim Ange had been ‘found out’ 11 games into last season, then you have to explain why Spurs improved this season across just about every metric, why Spurs win dramatically more points with a healthy center back pairing than without it, and why Spurs’ results and underlying metrics both fell off a cliff in both seasons at exactly the point at which our center backs got injured. All of that variance is not easy to explain while holding the manager constant, but it’s quite easy to explain while looking at injuries.

As you might imagine, key injuries require a squad to adapt and play differently. The case against Ange suggests that he’s failed to adapt to the conditions of injury crisis. But again I’ve shown that Ange has largely moved away from the hallmarks of ‘Angeball’ for more than a month now. We do not invert both fullbacks; we play long at much higher rates than before the injuries; and we’ve backed off from our intensive pressing. What you are watching when you say ‘Angeball is defensively naive and can’t cut it in the Premier League’ is NOT ‘ANGEBALL’ in any sense:

But perhaps Ange is responsible for Spurs’ injuries, due to intense training, intense pressing, and ‘suicidal’ tactics. This piece of the explanation relies on the assumption that Spurs are an outlier when it comes to sustaining muscle injuries, the types of injuries thought to result from explosive movements and intensive training and matchday tactics. It’s worth taking a look at.

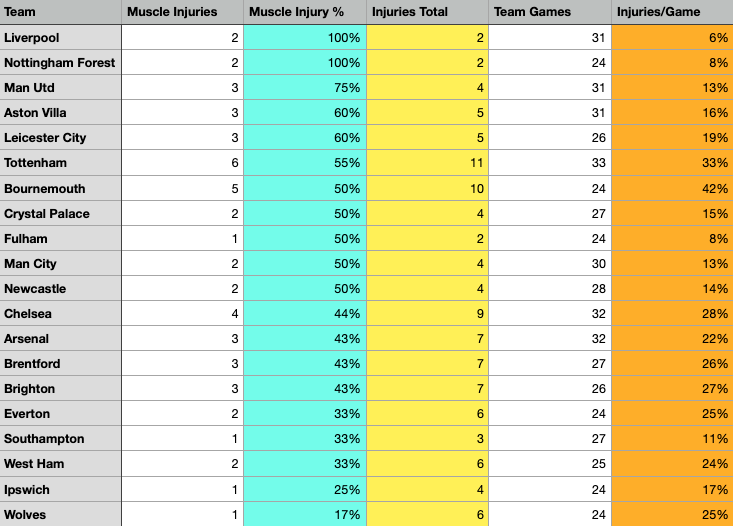

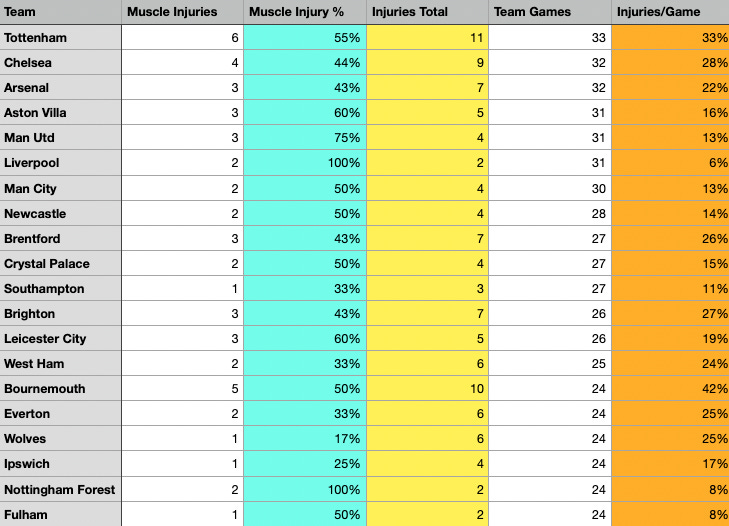

I’ve gone through Premier League Injuries, a source for injury news that aggregates Premier League injury reports, and made a Premier League injury dataset as of today, 20 January 2025. The table below is sorted by percentage of team injuries that are muscle injuries:

As you can see, Spurs have the most muscle injuries in the Premier League, but also the most total injuries. But Spurs have the 6th highest percentage of team injuries that are muscle injuries. Notably, for more than half of Premier League teams, 50% or more of their injuries are muscle injuries. Spurs at 55% are high, but not an outlier. Note also that Manchester United, playing lots of ‘pragmatic’ football, have a higher percentage of injuries that are muscle injures. Aston Villa play a pretty high line, also have a higher percentage of muscle injuries than Spurs.

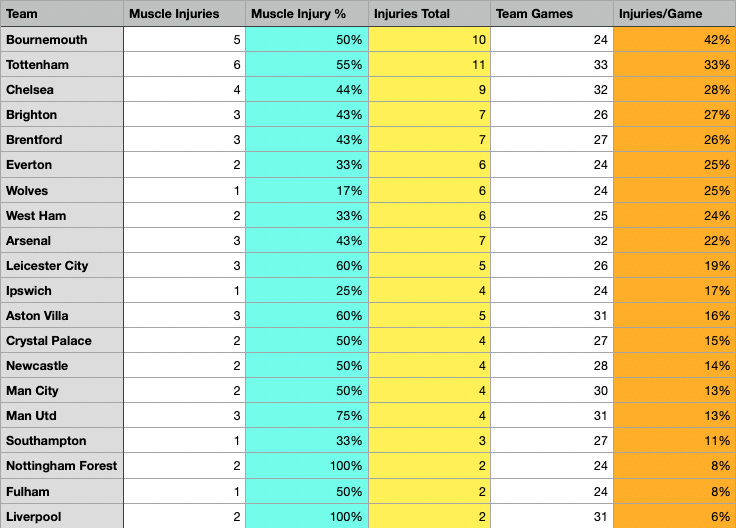

We can look at this a few different ways to provide more context. For example, you should expect team injuries—perhaps especially muscle injuries—to correlate somewhat with a higher volume of games. Spurs have played the most games so far of any team in the Premier League. The table below is sorted for team number of games:

So let’s have a look at the same table, sorted for injuries as a percentage of games played:

Here we can see Spurs are toward the top again—though significantly below Bournemouth, who also play an intensive style of football, and whose manager a lot of the Ange prosecutors want to replace him at Spurs—but again not radically different from the likes of Chelsea, Brighton, and Brentford. As you can see, the teams with the lowest injury percentage mostly have one of two things in common: either they’ve played very few games relative to those at the top (the difference in games played between the likes of Forest and Bournemouth at the bottom at 24 and Spurs at the top at 33 is 9 games, or almost a third more at the top than the bottom), or they have exceptionally deep squads. As I’ve argued many times, there’s really only one way to compete consistently across all competitions at the top level and contend for titles and trophies, and that’s to have a deep squad that can withstand the injury pressure of ever-increasing football matches at high levels of intensity across the league.

So here again I think it’s difficult to argue that Ange does something in particular that causes muscle injuries, even if media floated the theory when he was at Celtic. Like Newcastle last season, Spurs have just played a lot of football with a squad that isn’t deep enough and experienced enough to handle it without injury, and once the injures start to hit, they compound, as the few healthy players become susceptible to overuse. It’s fair to think a high-intensity style of training or of playing is partly to blame for Spurs’ injuries, but not fair, I don’t think, to say aberrantly so. In other words, lots of managers—top managers included—play a similar level of intensity and have a similar number and percentage of muscle injuries, so Spurs getting hit just a little bit harder in that respect is far from damning of Postecoglou.

In Summation

The above is not to suggest that the best explanation for Spurs’ poor results can’t be ‘a bit of both.’ Indeed, in my view, it’s a bit of both. But if we’re talking about whether to sack Ange Postecoglou, then we should have a firm explanatory sense of what’s causing the results. And in that case I think the evidence is pretty clear that injuries—not the manager or his tactics—contribute the largest share of the explanation.

You’ll no doubt notice that above I’ve given more words, more time, more charts to defending Ange than to making the case against him. You might think I’m showing bias in that way, and maybe to some extent I am (I’m biased by all the investigation I’ve done to come to my conclusions, yes). But there’s another reason for the imbalance, which is that so much of the case against Ange just comes down to pointing at the results, the simple view that we’ve taken from the outset as a fact of poor results. As soon as one starts to dig into explaining that view, it gets a lot more complicated and harder to simply pin on the manager.

Even if they had the comprehension skills to understand this (which I doubt), most of them are too far gone down the Ange out rabbit hole to be reasonable about it.

this needs to be pinned on subreddits and whatsapp groups